Alex Gilliam: Cheerleader of Possibility

Alex Gilliam is a national expert on K-12 design education and engaging children in redesigning and rebuilding their schools and communities. He is also the founder of Public Workshop, an organization dedicated to helping individuals, schools and communities achieve great things through design and maximize its potential as a tool for positive social change.

As per the Public Workshop website:

“Whether developing and leading unique participatory community design processes for the Hester Street Collaborative, redesigning the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum’s high school neighborhood research program to be more action-oriented; creating a process that empowered 350 K-12 students at the Sunshine School in rural Alabama to redesign and rebuild their decrepit school; or helping start the Charter High School for Architecture and Design in Philadelphia . . . Public Workshop has always sought to challenge, and redefine the boundaries of what’s possible.”

Tell us about Public Workshop, how it started & what you do….

For about the last 14 years I’ve been helping other organizations set up really innovative K-12 design education programs and/or help evolve their existing programs.

Originally that was primarily focused on much more formal design education—for example I helped start CHAD, a high school in Philadelphia for architecture & design, and set up a bunch of design education programs around the country, that were really more classroom-based, but in this relentless effort to be more effective at teaching and at reaching the kids I’m working with—and also to be happier in my own work—I began to question what the general person knows about architecture.

If we approach talking about architecture in terms of tapping into this emotional reaction, then maybe we can actually help them learn faster & better, we can have much more meaningful conversations, and we can get the average person much more engaged in the design process…

When I was at CHAD, at a certain point most of the kids we received came in performing below grade level. I realized that one of the problems might be that the way we generally think about teaching architecture, or design in general—this sequential way of learning, that you have to learn how to draw a line before you can draw a picture, that you have to learn about a pattern before you can make a building, all these sort of concepts before you can put something together…maybe this sequential way of learning was actually failing them…..and you know, that’s how all of our learning is constructed, at least, in most public schools. That really got me to question what the average person knows about architecture, and start thinking about it and doing a number of experiments.

When you or I walk into a public space, when anyone walks into a building, they have an immediate emotional reaction to it. When you walk into a Walmart for example, you have an immediate emotional reaction…..you don’t necessarily recognize it, and it sounds a little ridiculous, but the space will make you happy or sad, or upset, or angsty, or whatever. If I actually take the time to break down and ask you a series of questions about that space, you can tell me exactly, that “the ceiling’s too low,” or “the lighting’s too harsh,” “I don’t like the colors in here”….and if I was to take a group of say 10 people, minus some basic cultural differences, I could get a pretty good sampling, pretty good uniformity, of the problems that are going on.

I began to realize that the average person knows a lot more about architecture than we think they do, and if we approach talking about architecture in terms of tapping into this emotional reaction, then maybe we can actually help them learn faster & better, we can have much more meaningful conversations, and we can get the average person much more engaged in the design process than we actually do now, whether it’s a learning situation or redesigning a city.

I began to realize that the average person knows a lot more about architecture than we think they do, and if we approach talking about architecture in terms of tapping into this emotional reaction, then maybe we can actually help them learn faster & better, we can have much more meaningful conversations, and we can get the average person much more engaged in the design process than we actually do now, whether it’s a learning situation or redesigning a city.

That sort of relentless questioning, to try to do more, to have a greater impact, etc., particularly from that point on, has continued to roll, I guess you could say. I’ve delved further & further into questioning how we approach design in terms of getting people engaged, or learning about it, or even design innovation, i.e. how we designers approach trying to do better things. In subsequent years I’ve looked a lot more into this notion that our language systems, our sense of self, are very spatial—hyper-spatial—growing out of our sense of home, our sense of neighborhood.

Not only do planners today not have the right tools to get people excited and engaged, but they’re not being honest about where those people can really be beneficial.

The relentless questioning that came out of that teaching uniquely positions me to really fundamentally question the way that we approach engaging citizens, communities, neighborhoods in changing the places they live, and design processes or otherwise.

A lot of the current processes don’t work….in Austin for example they hired the most preeminent community participation firm to come in and do a master planning charrette for Waller Creek, and only 3 members of the community showed up for that…..you know, something’s seriously broken there!

I think a lot of it is this notion of accepting this orthodoxy of what people know & don’t know. At least in the case of public planning processes right now, the buzz word is participation, but the tools don’t really match the participation that they want. The tools right now are mostly surveys, and one-way community meetings that often turn into yelling matches, or are really boring….no one wants to do that anymore, it’s not meaningful, it’s not useful.

In my opinion, community kids are capable of contributing some really amazing things toward making the places they live better, but not only do planners today not have the right tools to get people excited and engaged, but they’re not being honest about where those people can really be beneficial. They’re generally saying, “Oh, we need participation everywhere,” instead of saying, “well, they’d really be useful here, here, here & here….”

So, for example, I did a community design charrette for a school on the lower east side of Brooklyn, to turn this outdoor swathe of asphalt into an outdoor classroom. I made it multi-generational, so I had, for example, the 75-year-old head of the Autobahn Society paired with a third grader from the school.

What was most amazing about that was recognizing and fully understanding that a third grader could really contribute something to the planning process, but of course the question was what……and mostly, we would say, “Have the third grader do some crayon drawings,” stuff like that, but you know…that’s not productive. It reduces the third grader’s contribution to a kid’s idea, and it’s kind of like just going through the motions—“Oh, the kid wants a slide.” Ok, great, whatever….

In the middle of this process the third grader stands up, and says “I want this space to be wonderful so it will not only inspire my classmates to do better…..to work harder and take better care of the school, but it should inspire the neighborhood to do better too.’”

Now, this is an under-performing K-5 school, in not a great neighborhood. There is no reason she would have heard the broken window theory before, but she stood up in the middle of the presentation and everyone’s jaw dropped. Now, if a third grader is able to recite the broken window theory without preparation or nudging, then what else can they contribute? And if it’s not a drawing, it’s ideas, and setting the possibility of a process.

So now I really focus on where, “where can kids, young adults, community really & smartly contribute to the design process of a place, a neighborhood, a building?”

One of the great challenges of education in the 21st century is establishing relevancy & meaning. One of the reasons that kids are as bored as bored can be is because there is little relevancy & meaning in education. We spend so much time trying to put the city into the classroom, which only under the best circumstances works, why don’t we actually make the city the classroom?

Within an educational day, if we can make what the kids are doing in their English or Geography or History class actually feed into a public planning process, and the kids recognize (and they do recognize!) that has impact, then they’re going to do better and the public planning process is better.

You’re not asking the kids to be designers—in a public planning process; they might be doing an oral history of the neighborhood that there’s not money to do otherwise, you know, uncovering stories of people & places that no one else could do.

So that’s making the public planning process better, but also, they’re working much harder in school because they find meaning in what they’re doing, and they’re being seen as useful. One of the most fundamental conditions of kids & teenagers is wanting to have control of the world around them…why not give it to them!!?

So, in that sort of way I’m trying to say, “how can we make school, and work, and the makings of our city all stronger? By making them messier again, and in many ways, that’s what I do, I guess…I have on my website that I’m a “cheerleader of possibility,” and that’s an odd sort of thing, it seems flip in a way, but I sorta’ am!

It’s sort of me trying to show by example and make connections between other precedents that I see, to show that education doesn’t have to quite be this way, the way your architecture firm operates doesn’t have to operate that way, it can be this way…..city design processes the same thing.

How did your formal education funnel into what you’re doing now? Case Study: Group Workshop at the National Building Museum »

I think that pattern recognition is absolutely essential to design work…out of kids, designers, community processes. The faster that they can recognize how or why a place is the way it is visually, how a design system is going together, the better the sort of thing that you can create.

Anyway, my parents and my History degree really helped me feel adventuresome in pulling together these disparate ideas that I don’t think most people are looking at in the same way. Also, while I was at UVA I was working with special needs children & adults, where I really had to focus on being entertaining & engaging, of having to maintain the attention of these 13-year-olds…

There’s this whole “genius” stigma with drawing. If you try to get people to draw they just shut down because they feel it’s not a very good drawing, because they think of Michaelangelo…but when they think of building something, well….people like using their hands.

What got you into teaching children with special needs?

I really like people, and well….getting paid to play is kind of wonderful! And that’s pretty much what I’m doing now. My research for my fellowship has proven inherently playful. I’m researching the National Building Museum’s architectural building toy collection, Erector Sets, Lincoln Logs, etc.—they actually have the largest collection in the country.

I really like people, and well….getting paid to play is kind of wonderful! And that’s pretty much what I’m doing now. My research for my fellowship has proven inherently playful. I’m researching the National Building Museum’s architectural building toy collection, Erector Sets, Lincoln Logs, etc.—they actually have the largest collection in the country.

I’m researching them because I see them as analogous to these making-oriented tools that we can use for better engaging people in dialogues about place, building and design, or actually using those tools to create better designs. People are tired of just talking, and often in these public planning meetings, or in education, it’s talking, or it’s contentious, or whatever.

There’s this whole “genius” stigma with drawing. If you try to get people to draw they just shut down because they feel it’s not a very good drawing, because they think of Michaelangelo…but when they think of building something, well….people like using their hands. They’re able to project themselves into something much more effectively, they’re not inhibited, and it’s also collaborative. It gets people working together, it gets people who come to planning meetings with their own agendas, who really just want to talk about their agendas…..it forces them to do something different, and see something in a different way. So, I’m looking to these building toys to develop new making-oriented tools for facilitating all these things—innovation, better learning, etc.

The experts better recognize the patterns that they’re building with, are able to expound on them faster, whereas the non-experts are not encumbered by those patterns. So they’re moving in different directions, but if you put them next to one another, then they’re going to influence one another.

So that’s the formal thing that I’m researching, but they have this Lego playroom there, and right now, honestly, that’s the much more interesting aspect of my research, because just going down there every day I notice these patterns that occur which really have deep implications for how we think about stimulating innovation.

For example, we think of copying & innovation as diametrically opposed, for the most part. But this research I’m doing, I’m looking at this free-play room where people are just building whatever they want with Legos, and there is absolute copying going on. There’s mainstream copying, so I see like a certain building pattern exist for a series of days, but then I see what the outliers are, like where people use Legos in ways that they’re not supposed to. And I try to go and talk to people about why they used the Legos in that way.

A Lego, even though it’s not made out of brick, it’s not heavy, its method of assembly implies a sort of thinking that’s brick-like, you know, putting them together like bricks. So when people turn a Lego on its side, or they don’t connect it at 90 degrees, that’s what I consider an outlier situation. When I go & talk to these people who have made these creations, it’s really funny to find out that they actually didn’t pull that out of their ass. To a tee, every one of them said, “Oh well I saw that somewhere else in the room.”

So what I started doing is going in and making my own outlier creations at the beginning of the day, to see whether I could stimulate or hack the system. I pretty much knew it would work, but even so I was gobsmacked when I walked backed in and this girl has copied the creations I did but simply turned the Legos on their side and in doing so had made this gorgeous multicolored ziggurat. These 10-year-old boys had seen what she had done and were so amazed by it that they then copied her and made a whole bunch of stuff with the Legos on the side—and it was fantastic!

So that has these deep implications for not only accepting that copying can be an explicit part of stimulating innovation, but that actually creating these situations where experts & non-experts are creating in the same space either together or next to one another can be hugely beneficial. Because we’re naturally going to copy, we’re naturally going to be influenced by the people next to us.

So in this case, the experts better recognize the patterns that they’re building with, are able to expound on them faster, whereas the non-experts are not encumbered by those patterns. So they’re moving in different directions, but if you put them next to one another, then they’re going to influence one another. I do think it’s important in my own work to be relentlessly observing, taking a risk, and just….trying it out, you know?

How did you start Public Workshop?

Public Workshop was 2 things:

1. Trying to give a name to everything I had done up until that point– even through grad school I continued to help other organizations set up innovative design programs. I kind of recognized that was a service I could continue to provide, and that I didn’t want to go work for someone else. I could have a much greater impact helping others do better.

1. Trying to give a name to everything I had done up until that point– even through grad school I continued to help other organizations set up innovative design programs. I kind of recognized that was a service I could continue to provide, and that I didn’t want to go work for someone else. I could have a much greater impact helping others do better.

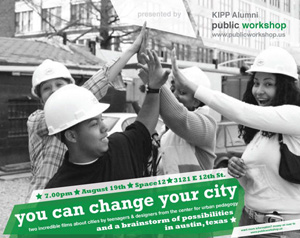

2. The other angle which was a direct benefit of grad school…..in May about two years ago I had put on a conference called You Can Change Your City, which was about getting people to talk about innovative processes and how they got there. That led me to get offered to speak at this Great Public Spaces citywide symposium in Austin. That had all these people from city government, congress, city planners.

I went up there and gave this presentation on “5 ways to change your city.” I had the crowd on its feet, I was stunned. People with much, much more theoretical experience were coming up to me and thanking me for sharing these ideas.

What was so compelling about it was that I tapped into this deep vein of people being tired of talking about things, and not just everyday citizens, but city planners who I’d never met before who told me that I gave them hope. I didn’t know what to say, it was almost embarassing, but on the other hand it was awesome.

So that, combined with this relentless questioning of “how we can get the average kid involved, to go out and change the world around them?” I realized I wasn’t going to be able to have a greater impact on kids until I could legitimately give them control over the world around them.

And then I went to the Rural Studio and found this K-12 school in the middle of nowhere, that communicated to the kids that no one on the state, local or federal level cared…..I mean, they were so embarassed by this school that no one would even mention it in public.

I went in there and created a process that empowered them to rebuild it . . . the first student govt. in the school came from doing this, the teachers were starting to look at the students in an entirely different way. The kids weren’t acting out, they were seeing connections between what they did and their younger siblings. There are some tremendous quotes I could give you about “Now I understand that I can do something will hopefully inspire my younger brother or sister to do something better, and they can look fondly upon what I did and feel that they can do something like that too.”

Honestly I feel it needed another 2 months for me to be there as an outside cheerleader saying “Yeah, you can keep doing this, this is what you do to get it fully standing,” but at the same time it was hugely successful for a number of reasons. It really helped me see the power of my basic intuition, which was, give people control over the environment where they live, work & learn, and amazing things can happen.

Honestly I feel it needed another 2 months for me to be there as an outside cheerleader saying “Yeah, you can keep doing this, this is what you do to get it fully standing,” but at the same time it was hugely successful for a number of reasons. It really helped me see the power of my basic intuition, which was, give people control over the environment where they live, work & learn, and amazing things can happen.

Also, interestingly enough, coming in as a designer, on one hand it taught me to be stronger + more assertive, on the other hand more humble—I was really distraught at one point that we had barely gotten to any of the design we had talked about doing, but on the other hand, realizing that we repainted 38 doors, the entire gym, the playground, we replaced windows, ceiling tiles, tore down derelict buildings, painted 8 murals, created a branding system for the school….and most of that was just basic labor! (laughs)

Were you managing that whole process? Everything?

Yeah but I created a process whereby they chose what they were going to do, and they chose how they were going to do it….but they still respected my role as an expert.

How did you streamline that creative process? It sounds like to a certain extent you were able to leverage your authority as an expert……in my experience as a project manager I’ve found it can be challenging at times when you get all these different cooks in the kitchen, often you’re not only dealing with reaching the right artistic decision but you’re also dealing with the politics of appeasing different people’s egos. When you’re dealing with politics and you’re dealing with all these kids, how do you streamline that?

(chuckles) Yeah….that’s hard! There’s no singular answer…being a good teacher, being a good designer, it all depends on knowing how to dance.

Right now we’re at the pinnacle of this period where the user-generated experience means everyone’s an expert, and also this notion, which I see all the time in education and community planning, “well if the community wants it then it’s great,” or “if the kid generates the idea then it’s great”…..well yeah, it can be, but if we go back to the conversation about Legos– recognize that sometimes outside stimuli can be really important for people to be able to understand what’s possible.

There are certain situations where as a really good designer, as a project leader, as a teacher, you absolutely have to step forward and put something out there that’s possible. Other times you have to step all the way back and let something happen….and other times you have to set things up so that you’re in the hot mess middle of it, creating together. The trick is knowing when you should use each of those, right? And that’s what’s hard.

Case Study: Build A 6-Foot Long Chocolate Cake Master Plan, Change A Place. »

There’s a post I did about this playground structure made out of tape—also a disassociative material! Cake— also a disassociative material! Sometimes these dissociative situations or materials are really useful for creating situations where not everyone is the “cook in the kitchen,” or everyone’s a cook in the kitchen together, in a way that ‘s really useful, instead of them coming forth and saying, “well this is my experience, and that’s what it’s going to be.”

Do you feel that the disassociative materials level the playing field, or they just force people to think out of the box?

Do you feel that the disassociative materials level the playing field, or they just force people to think out of the box?

That’s really important if you want to figure out how to get expert & non-experts to work together. I think having those disassociative situations where on one hand you’re stating who is an expert at what, but on the other hand you’re stripping away those titles so that people can better innovate. I’m really not interested in teaching a class anymore, for example, where I’m straight-up teaching—if I’m not sitting there solving it with the students that I have, no matter what the age, then it’s boring to me and also not very useful. Because I have expertise those kids have and they have expertise that I don’t have,

I think the value of the disassociative is creating situations where it’s about with rather than for, and understanding that that’s when innovation better occurs…..and those situations are hard to create and they vary from discipline to discipline. There are definite analogies in music and other fields.

Your team recently won the DIY Playground Design Competition, how did that come about?

All of that grows out of the process I mentioned…we created sort of a guide, not for building playgrounds per se, but for establishing a culture of making people go out and do things, of testing their public spaces and understanding what’s possible. Because a lot of the systems for making our cities are broken.

So really this about establishing an idea of what I call knowability, which is this idea that for most things, expect for maybe quantum physics, you can go out and if you directly and relentlessly interact with something, you can figure it out. But it really creates the establishment of an attitude of how you go about doing that, that risk is part of the game.

Six-year-old kids can make a three-story structure that’s totally safe, mostly on their own, if you develop an attitude with them of how you go about, not rules for safety, but…….you don’t need an adult to come up and tell you that “that’s not nailed on well enough,” lean up against it, shake it….you can figure that out.

People really want to be able to feel that too! With the mess that the government is right now, our cities, a lot of these massive institutions that have grown out of the organization age, where things were set up for maximum safety, maximum efficiency…those aren’t really working anymore. In the absence of those services that they provide, how do people fill in the gaps?

School teaches you to meticulously plan and go through all these processes, and doesn’t really establish this idea of risk-taking, and just going out and doing something and seeing what happens. I think this idea has been really beneficial, it’s helped these kids make that shift to realizing that they can approach learning in the neighborhoods where they live in an entirely different way.

So that DIY playground kit/guide is really a way, at least on a civic-design sort of level, of getting people to go out and test the places they live and start building things and trying to understand what’s possible. At the same time, challenging people’s perceptions—of risk, and of what it means to be a citizen, and of where things should go, you know? Our notions of risk in this society are totally messed up.

So part of it grows out of that one attitude of how we engage the city and how we engage people to do things, another part grows out of my intense efforts to figure out how to reach kids better, teach them about design, and so forth.

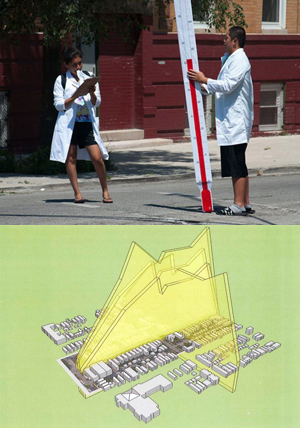

It really is reflective of this process I created, which radically transforms how quickly young adults are able to create great design. It shifts it fundamentally from being about bookish /classroom-directed learning to this notion of knowability, which goes back to what we discussed earlier, i.e. what the average person knows about space. Instead of having an abstract conversation about a public space in some office meeting room, miles away from where the space actually is, and trying to get people to deciper a 2D drawing about that spot, actually have that discussion in the place itself, and create tools for letting people explore that space, and you can rapidly accelerate how quickly they’re understanding how empowered they can feel about creating good design and be engaged in the place they live.

It really is reflective of this process I created, which radically transforms how quickly young adults are able to create great design. It shifts it fundamentally from being about bookish /classroom-directed learning to this notion of knowability, which goes back to what we discussed earlier, i.e. what the average person knows about space. Instead of having an abstract conversation about a public space in some office meeting room, miles away from where the space actually is, and trying to get people to deciper a 2D drawing about that spot, actually have that discussion in the place itself, and create tools for letting people explore that space, and you can rapidly accelerate how quickly they’re understanding how empowered they can feel about creating good design and be engaged in the place they live.

A lot of the kids that I developed that process with are very diverse, some of them are incredible thinkers, but they feel so hesitant about going out and doing things. School teaches you to meticulously plan and go through all these processes, and doesn’t really establish this idea of risk-taking, and just going out and doing something and seeing what happens. I think this idea has been really beneficial, it’s helped these kids make that shift to realizing that they can approach learning in the neighborhoods where they live in an entirely different way.

With all these different projects, do you find yourself working with a lot of the same people over & over again? With Public Workshop, do you have a certain division of labor within your team?

No…it’s hard to say—Public Workshop is largely me, but it varies—I’m acting largely as a consulting firm, so it inherently involves people from each of the organizations that I work with, and I have these great collaborators, such as the Chicago Architecture Foundation, and Open House New York, and now this firm in Austin, etc. Ultimately, once I become place-based I would love to build a practice that mirrors how I work.

I would like to bring on more young people, to have Public Workshop fundamentally reflect who I work with and how I work. I have this 19 year old intern named Brenda who’s a superstar! I brought her on when I was working for this firm in Chicago to help convince them what was possible, and I was also happier as a result having her around, and I was able to do better work. So why not have my business model reflect that…but I can’t really do that until I’m place-based in a substantial way.

How do you support yourself….if you don’t mind me asking!

It’s project-to-project. One of the best pieces of advice I ever got was at the Rural Studio, my advisor said “Go where the feedback is good.” Do whatever you can to maintain and grow those best relationships that you have. I wrote an article about my friend in Chicago and this fantastic design firm called Firebelly…she said her whole attitude is, “do good things and good things will come to you.” Largely, that’s what I try to do.

You mentioned becoming more place-based….

It became apparent to me that I need to evolve to the point where I’m creating my own programming. A lot of what I do is, fortunately (for me because it’s exciting) or unfortunately (because it’s not always easy to pay for), far enough out there that I have to create the culture within institutions/cities/places, to pay for that. And I usually have to do a lot in advance and/or wait a long time to convince people to do that (chuckles)…that’s the way I’ve been operating.

Personally, I know that although to a certain extent I’ll be parachuting into places for the rest of my life, and getting to work on great projects with great people, I work best with deep face-to-face connections, i.e., having a neighborhood or community of people that I trust and work and experiment with on a local basis, and can take great risks because I’m committed to that place and can evolve and problem-solve as I go along.

Personally, I know that although to a certain extent I’ll be parachuting into places for the rest of my life, and getting to work on great projects with great people, I work best with deep face-to-face connections, i.e., having a neighborhood or community of people that I trust and work and experiment with on a local basis, and can take great risks because I’m committed to that place and can evolve and problem-solve as I go along.

In doing so I can create really blatant examples where I’m showing how radically different things can be done, so I don’t have to spend so much time working with new clients and explaining to them what the culture could be, developing the culture for different things, I can be showing them just by doing it on my own.

You can keep up with Alex’s endeavors at Public Workshop.