Daniel Power: CEO powerHouse Books, Co-Founder, The NY Photo Festival (Pt. 1)

Daniel Power is the Founder/CEO of powerHouse Books, a world-renowned publisher acclaimed for its diverse publishing program and its ethos of perpetually challenging popular conceptions of the role of the “art book” in contemporary culture. He is also the Director and Co-Founder of the New York Photo Festival, an annual event dedicated to the “Future of Contemporary Photography” which draws thousands of people every year from all over the world.

I met up with him one night in DUMBO, Brooklyn at the powerHouse Arena, the 5000-square foot “laboratory for creative thought” which hosts not only the publishing house but also a thriving gallery, bookstore and event space. We discussed his evolution into a groundbreaking publisher/curator and gleaned some advice for aspiring creative professionals.

Tell us a bit about your background and any early people or experiences that influenced you.

Tell us a bit about your background and any early people or experiences that influenced you.

A formative experience was my childhood in Washington D.C. I was born in the early sixties, the oldest of five children. My father worked in the Justice Dept., both he and my mother were pretty good about bringing us to cultural events on the mall, be it fireworks, or folk festivals…there were a lot of protests going on at that time as well.

That always struck me as a fascinating experience as a young child, going to these events—large gatherings of people listening to music, seeing shows, seeing performances. There were also funerals—MLK, RFK, there were a lot of strong political things going on at the time. I remember going to flower shows and having to evacuate because of bomb threats.

I think that’s why I’ve always been somewhat captivated by spectacle—the size of crowds and events, and the ability to command a focus from a giant group of people to one subject, be it a speaker or a show of some fashion.

Julia Child’s 100th Birthday Celebration at the powerHouse Arena (Photo: 52 Projects)

Ideas didn’t have a lot of currency, and they don’t for the most part in the Midwest. Loyalty, experience and paying dues have a greater currency, and that to me seems like a waste of human potential.

When I was nine I moved to the Midwest and things were very quiet for a very long period of time. Things were not as dynamically, culturally incessant as the East Coast is.

Why did you move to the Midwest?

My father wanted to take a teaching position in Iowa, which is where he was from, so he moved his family back, to live in a large house and have his kids run around on a lawn. I was going into the 4th grade, and it was like going into the 3rd grade. That’s how advanced the schools were in D.C. at the time.

Photo: Matthew Lomann

After graduating from the University of Iowa I moved to Chicago with my girlfriend of the time and even that was too Midwestern for me.

Chicago’s a really big city, but it still has a Midwestern mentality. There’s something that really bugs me about it. You couldn’t just have a really good idea, pitch it and follow through and deliver…you had to “pay your dues.” Ideas didn’t have a lot of currency, and they don’t for the most part in the Midwest. Loyalty, experience and paying dues have a greater currency, and that to me seems like a waste of human potential.

Stuart Brent was sort of my first exposure to the power of a brand—it wasn’t the books themselves, it was him. His space, and what it represented, that made it what it was.

When you were in Chicago, you were the manager of Stuart Brent Books. How did you get started along that career trajectory, were you always fascinated by books?

Stuart Brent, 1985 (Photo: Chicago Tribune)

The main reason he hired me was because I was Catholic, he figured I wouldn’t steal from him (laughs), as he was having problems with employees that weren’t very honest. This was one of two times my Catholic upbringing landed me a job.

The bookstore was a very dynamic place; it was downtown, there was a lot of foot traffic, a lot of the Chicago cultural elites and intelligentsia, especially from the University of Chicago. People came in to be told what to buy—“What are the new books I should be reading?” Stuart also had a book club, about 300 people who would purchase a book at his recommendation, at full price, every single month.

…being in a place like that, where people are being told “it’s an important book, you should pay attention to it” was enough to make someone buy it…

Stuart refused to organize the books—it was a mish-mosh everywhere with no signage, you had to memorize the store. One day he got very upset when he saw that we had placed a limited edition of The Odyssey among the classical works. He proceeded to pick it up and shove it between a bunch of bird books on a shelf right by the register, at eye-level. The rest of us thought, “This is insane, it’s not with the other books!” …but a week later, it got sold.

The point was, it doesn’t matter, it’s where people will see it, and being in a place like that, where people are being told “it’s an important book, you should pay attention to it” was enough to make someone buy it. I thought, “Wow, that’s something.”

So carefully—and not so carefully—curated disorder actually worked for this particular retail store.

Stuart Brent with Studs Terkel, Robert Parrish, Stephen Spender, Jack Conroy, Nelson Algren (Photo: The Seven Stairs)

It was the strength of Stuart Brent’s character, personality and history of being an idiosyncratic bookseller and pals with some famous writers—Saul Bellow, Nelson Algren. That’s what people were buying.

Stuart Brent was sort of my first exposure to the power of a brand—it wasn’t the books themselves, it was him. His space and what it represented made it what it was.

During that time, were you interested in Photography, or anything like that?

During that time, were you interested in Photography, or anything like that?

No.

What was your dream or aspiration at that time?

I did not have a dream! I had a girlfriend, I was hanging out in Chicago in the early/mid 80s, having fun.

I started out part-time at the store but was promoted to manager pretty quickly, because I was doing things people had not done for years, like returning stuff that had been there for a long time. I returned it to book publishers and made Stuart a lot of money in return credits, and he was ecstatic. So he made me manager, and everything was fine.

I began thinking about trying to find a “real” career job. I had graduated with a History degree, and was thinking about becoming a History professor. Around that time my girlfriend and I broke up, and a book publisher by the name of George Braziller visited the store from New York City.

Braziller back in the day had published some very famous Surrealist works and had founded a very successful book club. He learned that I wanted to get out of Chicago, and offered me a job as a Sales Manager.

So I moved to New York to learn how to work on the publishing side of it.

East Village, New York

That must of have been exciting, since you were itching to get out of the Midwest…

It was, although I didn’t really know what to do once I got here (laughs). I just started talking to sales reps and giving them sales information doing the best I could.

The job only lasted for four months. My second day there this old lady said “Don’t get too comfortable” and as much as I tried to do what I thought I should be doing—I didn’t get a lot of direction—Braziller decided that maybe he didn’t need a Sales Manager after all.

So at that point I’d only been in New York for a few months and needed a job. I tried working as a bike messenger, it was a shitty way to make a living but sort of fun…until I got hit by a taxi cab and totaled my bike.

Yikes!

Yeah. It was ’88, I was sharing a 2-bedroom in the East Village with a drummer, which made job-searching difficult. He didn’t play anywhere, but he would wake up in the morning, get his breakfast, and then come back, put sheetrock over the windows, and play. He would play from 9:30 in the morning until 6 in the afternoon!

Yeah. It was ’88, I was sharing a 2-bedroom in the East Village with a drummer, which made job-searching difficult. He didn’t play anywhere, but he would wake up in the morning, get his breakfast, and then come back, put sheetrock over the windows, and play. He would play from 9:30 in the morning until 6 in the afternoon!

We had one phone, I don’t think we even had a voice machine, I couldn’t use my own apartment to make phone calls, I would have to go out to libraries and phone the want ads, looking for work in publishing.

Eventually I landed an interview at Aperture. Their director at the time, Michael Hoffman, a closet mystic of sorts, asked me what my sign was and read that I went to a Jesuit college for two years, and hired me on those two bases.

He hired you based on your sign and the fact that you’d gone to Jesuit College?

Yeah.

God bless that Catholic upbringing!

(laughs) It’s good for something I guess…

“That magazine, this newspaper, this blog, this film festival…there are all these sources of authentication, because people ultimately need to be told what is good and what should be paid attention to.”

Aperture in ‘89 was the only well-known photo book publisher aside from the New York Graphics Society. Photography at that time was kind of cheesy…everything was printed on glossy paper, 4-color, sometimes reproductions were good, more often they were not.

Aperture had some very good books…the content was more intelligent, it was very provocative from an artist perspective, but the market was minute, because photo books and photography just didn’t register in the public consciousness. It was Ansel Adams, or nothing.

Aperture had some very good books…the content was more intelligent, it was very provocative from an artist perspective, but the market was minute, because photo books and photography just didn’t register in the public consciousness. It was Ansel Adams, or nothing.

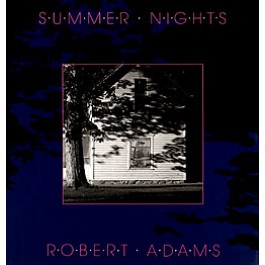

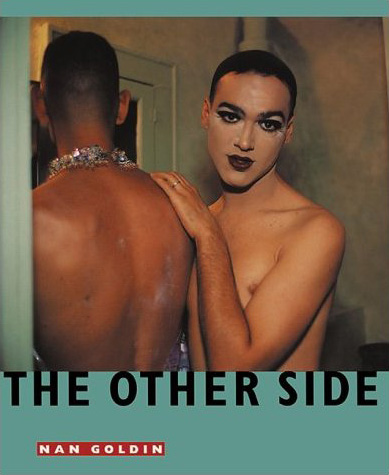

I worked for Aperture selling their books, prepping the sales reps. I started looking at the books and learning more about photography…some of these books blew me away. I remember going to the basement trying to find something and finding these old archival editions. I discovered work by Diane Arbus, Robert Adams, Nan Goldin.

Robert Adams had these seemingly similar photographs of nature, but there was something very subtly compelling about each one that made it different, and the whole project made me think…and then looking at these amazing Diane Arbus portraits that were photographed in a way that I just didn’t even understand at the time, but that made them irresistable. I remember just being really impressed by that.

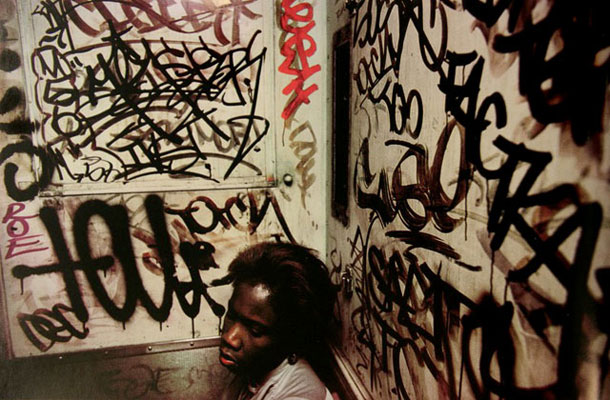

Bruce Davidson’s Subway was something that people just really didn’t understand at first. These gritty, dramatic photographs of the New York subway.

Why do you think that people didn’t get it?

At any stage in development of the common mindset, people are prepped to understand and appreciate the value of something that’s been prepared for them or mediated to some degree.

At any stage in development of the common mindset, people are prepped to understand and appreciate the value of something that’s been prepared for them or mediated to some degree.

I think people are much more attuned to sophisticated, conceptual photography and other forms of art now then they ever have been in the past.

That probably has a lot to do with the democratic explosion of mediums—digital, there’s so much now, there are so many sources that are citing people that no one knows about, that it almost becomes a contest to find new things, have them featured somewhere, and have them know that they get the sort of seal of approval. That magazine, this newspaper, this blog, this film festival…there are all these sources of authentication, because people ultimately need to be told what is good and what should be paid attention to.

“I think it confused people. Who are these people, with their hair down, and their bruises, weird portraits of unattractive people, self portraits of a woman who got beat up, ya know?”

In the 1980s there was no source, at all. You had the NY Times Book Review and that was it. They would pick up a photo book once a year, during the Christmas round-up…that was it. And even then photography was buried in the “Art” section, from a sales perspective it wasn’t even considered its own genre. Everything was in “Art.” If it was oversized and had pictures in it, be it paintings, line drawings, monographs, installations, it was “Art.”

Photography as a genre didn’t start to break out on the bookshelf in the book retail industry until the late 90s.

Photography as a genre didn’t start to break out on the bookshelf in the book retail industry until the late 90s.

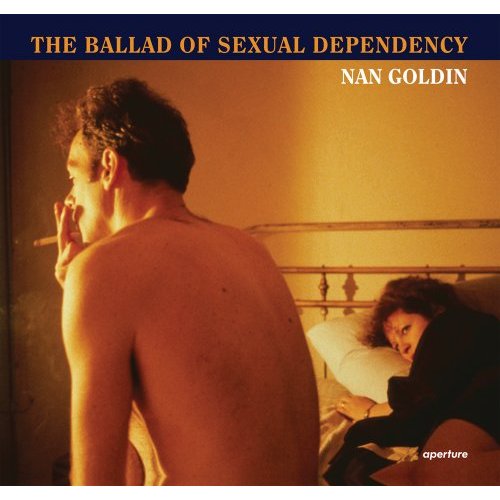

In the 80s Bruce Davidson and Nan Goldin were considered weird, like “what the hell’s this?” Aperture in 1988 published a hardcover of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, they printed about 3000, which at that time was a very small print run, what did they sell? They sold like 1000 copies.

I think it confused people. “Who are these people, with their hair down, and their bruises, weird portraits of unattractive people, self portraits of a woman who got beat up, ya know?” No one got the aesthetic of real life, self-documentation, experiential photography of the kind that Nan was involved with…

The paperback came out, it didn’t sell, the Executive Director of Aperture allowed me to organize a book signing at B. Dalton in the Village. B. Dalton was an anomaly because they had book managers that in those days could still buy books directly that related to the Village, and I’d go around to book stores and meet people, I’d get them excited about this book, which I thought was incredible, really mind-blowing.

What was your drill when you’d go around to these places?

I’d go to these booksellers, tell them who the artist was, tell them why the artist was important, get them excited about the work. We ended up doing things that we’d never done before, like create a collage, put it on foamcore and stick it in the window. Window displays…nobody did that back then.

We arranged a signing, it was Nan and I, and David Armstrong was with her…and no one was there. They made an announcement, and no one came…she was mortified. Eventually some of her friends showed up…

“We went from an idea to, after 4 years, doing 4 million dollars a year. We were warehousing our own books, selling them, it was pretty chaotic…”

How did you co-found D.A.P [Distributed Art Publishers]?

I stayed at Aperture for a year and a half doing sales & marketing but they wouldn’t give me a raise so I left. New York being New York, I met other people, did some freelance work here & there. I was hired by Parkett on a consulting basis, helping to sell their art magazine into bookstores. I worked for Artforum as a circulation director.

Eventually I met Sharon Gallagher, who had left Abbeyville to start her own company, and we decided to combine forces and make a distribution consortium. This was 1990.

Eventually I met Sharon Gallagher, who had left Abbeyville to start her own company, and we decided to combine forces and make a distribution consortium. This was 1990.

Sharon ran the business side of it and I did the sales & marketing. We teamed up with Parkett Art Magazine, particularly co-founder Walter Keller, who went on to start Scalo, which throughout the 90s was the most influential photo book publisher in the world.

When Walter first started he asked me what sort of photographers I liked and I told him about Nan Goldin, Robert Frank, Larry Clark…a lot of these photographers I admired who had been let go by Aperture.

The very first book Walter did from scratch was the 1992 Nan Goldin book The Other Side, and that was an immense success for Scalo…and for D.A.P. From then on photography books were the lead titles for D.AP..

We went from an idea to, after 4 years, doing 4 million dollars a year. We were warehousing our own books, selling them, it was pretty chaotic…it coincided with the advent of the “super-stores,” which boosted sales tremendously.

“I knew I could sell, and explain to book buyers why things were important…to be that voice of authenticity, to give someone permission to appreciate and get behind something.”

As far as spearheading this new venture…were you just sort of winging it?

Starting a company and saying “we’re going to expand this, and do that,” that was all winging it, but taking a bunch of book projects and samples and going into a store and convincing the bookseller why they should buy these books, that was easy to do, I knew how to do that. I knew contemporary art from working at Parkett, I knew photography from working at Aperture. I knew I could sell, and explain to book buyers why things were important…to be that voice of authenticity, to give someone permission to appreciate and get behind something.

We worked really hard to get the books seen in the right places…I’d go in and make a presentation to the old guy who wouldn’t understand anything, and then once he’d leave I’d make deals with the assistant buyer who knew what I was talking about and would place these books at the tables. Back then the designers and photographers and cultural tastemakers would go into these spots and see these books right there and a lot of times they’d buy it….that, and just them seeing it around, displayed prominently and conspicuously created this buzz that would sell a book.

“Learning how to make a good book is difficult. Going into it I knew how to sell but nothing beyond that . . . it was a sharp learning curve.”

With all of D.A.P’s success, why did you leave to start powerHouse Books?

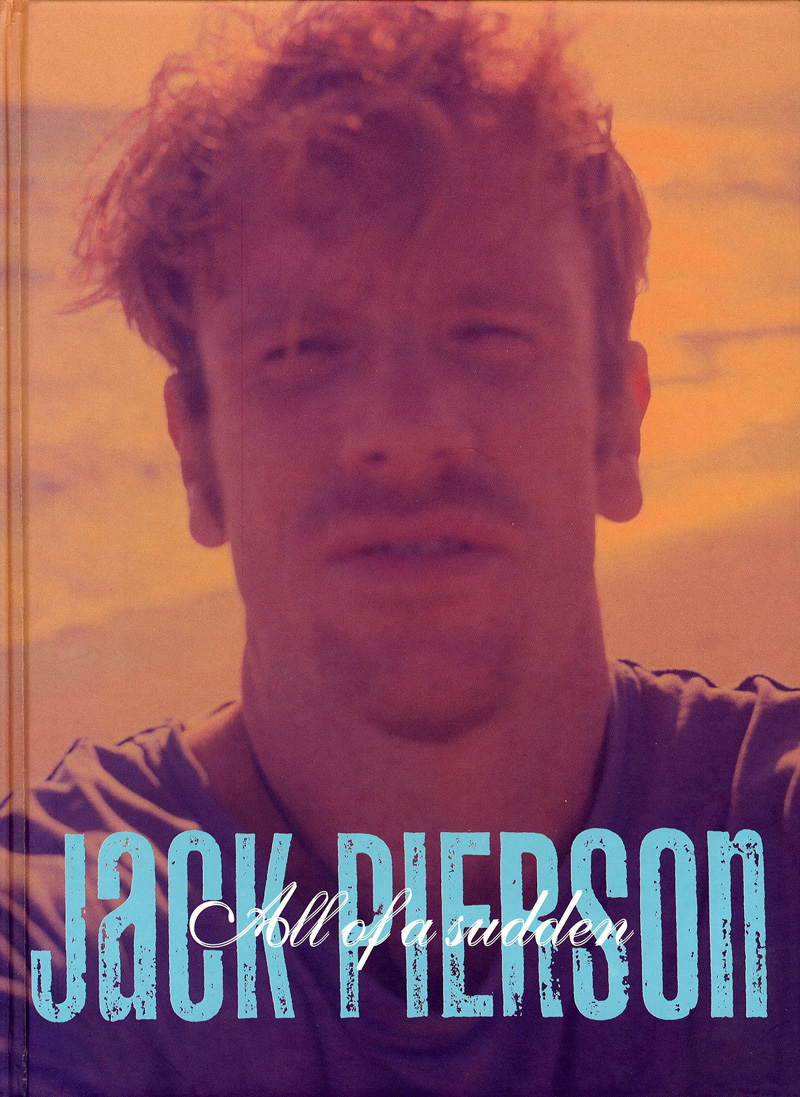

Sharon and I had disagreements about the structure of the company and where it was going, so in 1995 I decided to leave and start my own company. I sold my interest back to D.A.P, got some money and published my first book with it, Jack Pierson’s All of a Sudden.

Sharon and I had disagreements about the structure of the company and where it was going, so in 1995 I decided to leave and start my own company. I sold my interest back to D.A.P, got some money and published my first book with it, Jack Pierson’s All of a Sudden.

Learning how to make a good book is difficult. Going into it I knew how to sell but nothing beyond that. I had to learn how to make a contract, how to design and produce a book…it was a sharp learning curve.

Were you creative-directing the book, or partnering with the right people? How did that work?

In this case it was a joint venture with Thea Westreich, who wanted to publish a book by Jack Pierson and needed a sales partner to do it. As far as the creative direction Jack Pierson knows his work extremely well, he basically art-directed his own book with Tony Morgan, the designer of the time.

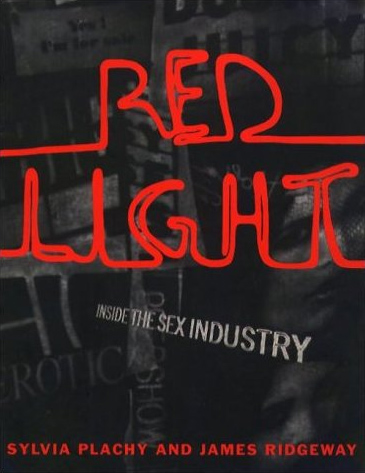

It was the first artist book that I did, and because Jack was on the rise in the world of fine art, it sold really well. Based on that and the sell-back to D.A.P I started a project, Red Light, which was a photo essay by Sylvia Plachy and Jim Ridgeway about the sex industry in New York and New Jersey.

You were..thirty-three?

Thirty-two, thirty-three, somewhere around there. That was a raw project…merging these long essays, photography and research into a package that worked was really tricky.

Thirty-two, thirty-three, somewhere around there. That was a raw project…merging these long essays, photography and research into a package that worked was really tricky.

I got introduced to Yolanda Cuomo, a designer, and for the better part of a year I just watched how Sylvia and Yolanda worked…how the designer worked intuitively, reacting to the photographer’s inclination, and taking the photographer talking about something and translating that into a printed form, a left and a right page. It was pretty amazing.

I learned fast. I learned how to resize pictures and talk to the designer, I learned how to edit. I had to bring the book down to 256 pages from 287, I went in by myself on Quark 3 (laughs) and learned to kern, adjust leading, format type, move pages and I brought the book down to 256.

With later projects I learned about separations, paper, texture, controlling press…and that was a traumatic experience (laughs). You have to make sure this book is perfect, and you often have these large black photographs with all these gradations of gray, and you have to make sure that it’s a very smooth curve…

During this time was powerHouse your main gig?

It was my main gig, it was two of us—me and Craig Cohen– from ’96 to 2000, 2001. There were a lot of great times…we’d make a book and then go sell it.

Craig is still with me, I hired him in ’96 right out of college, almost as an intern. I taught him how to print, he learned how to separate, how to project manage, and now he’s more or less running the company.

Craig Cohen & Daniel Power with Jessica Lange in 2008

“In 2000, 2001 these really interesting small boutiques starting popping up selling skateboards, hip hop clothing. They were very tightly curated…it broke the mold in many ways for clothing, for streetwear, for sportswear…”

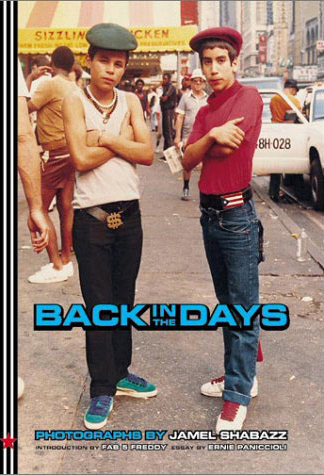

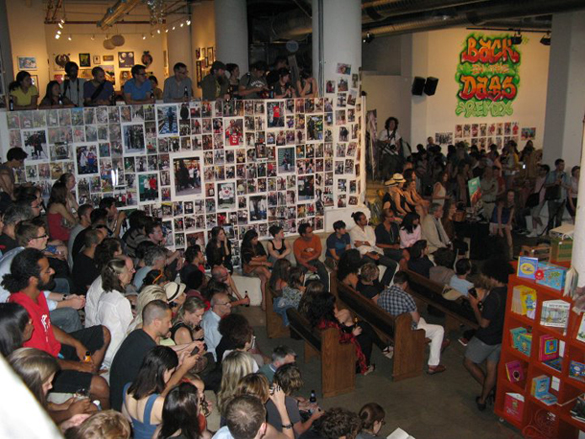

Craig Cohen signed the Back in The Days book by Jamel Shabazz, right?

Yes, he and Sara Rosen.

That was the one of the first books where the physical condition of the artwork and the large-scale monographic treatment to the work was less important than the design of the book and the content of the image.

That was the one of the first books where the physical condition of the artwork and the large-scale monographic treatment to the work was less important than the design of the book and the content of the image.

There are many instances with photo projects where the original artwork is not in the ideal condition, maybe it’s washed-out polaroids or snapshots, but you find the content so compelling that you have to do something…so you work with the elements, the weaknesses almost, to extract the positive.

It’s a great book…it took everyone by surprise. It’s an example of where book publishing and developments in pop culture—especially retail—sort of coincide.

In 2000, 2001 these really interesting small boutiques starting popping up selling skateboards, hip hop clothing. They were very tightly curated…it broke the mold in many ways for clothing, for streetwear, for sportswear…these places were the ones that really picked up on this book.

We saw no movement in the book trade…the book came out, sales reps didn’t sell it, it didn’t go anywhere, but then phonecalls started coming from places we’d never heard of—Alife—they’re taking 100 copies, and we’re like “what the heck is this?”

The first print run was very small and practically all of it went to boutiques. So did the second print run. And then some of the leading cross-genre bookstores that also sold cultural, youth-oriented stuff started ordering it. It started creating a snowball effect. And then 2-3 years later the NY Times called the book a “cultural touchstone. “ It’s sold consistently for ten years, and last year we came out with a remix with additional content.

We knew that . . . people would come in and just be inspired, either by what’s on the wall, on the table, the cabinet, or who’s reading or talking or doing a slideshow…

In addition to its diverse publishing program, powerHouse is known for throwing events and exhibitions…how did that come about?

Around 2003 we were in an office building on Varick Street. One day I saw this “For rent” sign on this space across the street—an an old envelope factory/warehouse—and we made a deal to rent the first floor.

We thought it would be exciting to add a gallery component to what we were doing, to do shows in the front and sell art, and have the publishing company in the back. We had saved up some money after the New York September 11 book so we put down wood flooring, white walls, made it look like a real Chelsea gallery. It was 800-900 square feet for the gallery, the rest was the office.

We thought it would be exciting to add a gallery component to what we were doing, to do shows in the front and sell art, and have the publishing company in the back. We had saved up some money after the New York September 11 book so we put down wood flooring, white walls, made it look like a real Chelsea gallery. It was 800-900 square feet for the gallery, the rest was the office.

The parties we would have, the book launches, became kind of legendary. We sold a lot of books…occasionally we would sell some art, but we found out quickly that we sold more books than art.

Two years later the owners sold the building and we had to find a new place. We got hold of Two Trees Management who showed us around Dumbo and the last place we saw was this massive space—the current space now, the Arena. They had planned to cut it up into 4 spaces, they wanted to know which part we were interested in, and we were like, “we want the whole thing.”

Did you have to pitch them on what you were going to do?

We told them our idea, which was to have a larger bookstore downstairs with regular book signings and events and then the publishing company on the mezzanine. They got it right away. They gave us a 10-year lease, and we were able to swing it.

When we first moved in we had this big event that coincided with VH1 Hip Hop Honors Week, and we managed to get the place ready an hour before the grand opening happened. We had about a thousand people, and the owners were very happy. We brought in all these graffiti artists, we borrowed scaffolding, it went all the way to the ceiling. It was an amazing installation.

No Sleep 'til Brooklyn, 2006 (Photo: DumboNYC.com)

We just told them that we would do our shows and sell our photo books. At that time it was 2006 and the market for photo books was really strong.

Easter Frolic, Kids' Party, 2011

About half a year later my wife asked for a table to sell some kids books, and that table became two, three, four, and people starting noticing them and they started having a reputation onto themselves.

That grew into fiction and nonfiction, and then we had an illustrator of a kid’s book come in, and then we had an author come in and read, and that started to really take off, in 2008/2009.

Bomb Magazine Launch, 2011 (Photo: Alex Martin)

How are you going to look and learn, and feel a book just by looking at the cover online? It makes for a much more ruthlessly efficient way to consume printed material, but it has killed the the visual, peripheral experience…which I think we have brought back in the Arena.

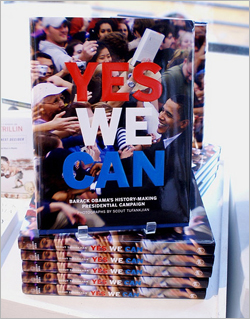

We were still doing these really intense exhibitions, we published an Obama book in ‘08 after the election and we had a huge exhibition that did really well.

We were still doing these really intense exhibitions, we published an Obama book in ‘08 after the election and we had a huge exhibition that did really well.

I would imagine that that book did really well…

It did, but that was the beginning of the recession, so a lot of those books came back in ’09. If this had been four years earlier that would not have happened. Already in late ’08 things were not looking good…and photo books ultimately died.

Around 2008/2009 the book retail market went through a purge and never recovered in many ways. The chains got more sophisticated figuring out what the turnover rate was per shelf space, and since the mid-90s that shelf space for photography kept getting smaller and smaller. Today the photo buyer position is gone.

That’s because the photo books weren’t moving?

Not fast enough. And now it’s mixed in with “Art,” just the way it was in the late 80s. That’s IF you can get a book into Barnes & Noble. Of course nowadays everything goes through Amazon. Most publishers sell their stuff through Amazon. So instead of going to Rizzoli and seeing these wonderful tables and perusing, all you get is suggestions on the Amazon site.

Photo: Chris Talbot

…which I think is why sales for us are really not bad…people come in and are impressed with the size, they are inspired a bit.

So you would say that the space element, the live element, has engaged people on a whole other level?

We knew that would be the effect, that’s why we called it initially the laboratory for creative thought…people would come in and just be inspired, either by what’s on the wall, on the table, the cabinet, or who’s reading or talking or doing a slideshow. And people want to collect something of that experience.

Our instinct was that that would work in our favor and it has—first with photo books, then children’s books, then fiction and nonfiction.

We still sell powerHouse books, but now the majority of movement is in the fiction, non-fiction, children’s books. And that’s because the buyer—my wife—has gotten really good at cultivating intelligent choices that we stock in store.

123 Comments

Loved reading the interview; it is inspiring in itself, and I look forward to Part 2. Daniel Power is a good example of someone who followed his ideas and instincts to make important contributions to our culture and who continues to grow and change with the times- even when things seem bleak.

Inspiring article. A testament to what can be done with your passion, drive, and chutzpah. Looking forward to the next…